Published in Lake Country Journal, August/September 2016 Edition

Written by Tenlee Lund | Photographed by Andrea Baumann

A century is a long time, especially in the horse world, where the animals’ tasks have evolved from mainstays for transportation and farm work to more discretionary uses. Yet Larry Curell’s family history with horsemanship goes back more than one hundred years. His great-grandfather was a member of the U.S. Cavalry.

Larry picks up a black-and-white photo of his grandfather, Russell Underwood, his uncle Larry (his namesake), and himself as a boy, and says, “That is what started it all. Three generations—that was the root of all of it right there.”

Larry grew up on a working ranch, breaking horses, and branding cattle. His grandfather had a blacksmith shop in the back of the barn. “The way I see it, it’s a lost art. I grew up with it and took a lot of pride in it.”

He’s the only one from his generation who stayed in the industry. His brothers, sister, and cousins all chose different paths, “but I wanted my kids and my grandkids to understand what it is to grow up raising animals and understanding animals and having that love for them like I do.

“Sara grew up in a barn,” he says, remembering taking his oldest daughter with him when she was six months old. While other kids were playing video games, “my kids were cleaning box stalls and taking care of horses.”

Son, Cody, has been going along on farrier calls with his father since he was six years old. Larry says, “I’ve had him pulling shoes since he was eleven and trimming since he was fourteen. I had him nailing shoes on by the time he was sixteen, the same thing my grandpa did with me.”

Cody laughs, saying, “It was a big learning curve.” The first time he pulled the shoes off a horse, the animal stepped on his foot and smashed his toe. The first time he actually nailed shoes on a horse it took him two-and-a-half hours to get the first one on—and his father made him pull it off because it wasn’t done right.

Now father and son have developed a seamless partnership. The work flows between them effortlessly, even as they trim and shoe twenty-five horses in a day. “The connection is incredible,” Cody says, trying to explain how they work so closely that one knows what the other needs when neither has said a word. “The last couple years have been like that. When I first started, it was not like that,” he laughs.

The three—Larry, Sara, and Cody—have all fallen in and out of love with aspects of the horse industry before coming together to form the nucleus of the Curell businesses. Larry actually quit shoeing some twenty-five years ago after he burned out on the business. For two years he worked in construction before customer demand—and his love for the animals—brought him back.

Cody trained to be a diesel mechanic but after six months of “the same thing every day,” he was bored. He came home for a summer, started shoeing horses, and “that was it. You can see new places every day and meet new people.” He was hooked.

Sara enrolled in a pre-veterinary program but, as she shadowed female veterinarians, she “realized they didn’t have families.” This triggered some soul-searching and led her to chiropractic medicine. Eventually Dr. Sara became the first certified animal chiropractor in northern Minnesota. She works on horses, dogs, and cats in addition to people.

“She’s really improved our business,” says Cody, although he admits he was skeptical at first. “When she came home with all that chiropractic stuff I thought it was just a joke.” Then she successfully adjusted the shoulder on his roping horse and “that horse went off like a million bucks.”

Now Cody says Sara’s contributions have “taken our business to the next level.” She’s also saved her brother and father from some physical encounters with horses that can weigh a thousand pounds or more. If a horse doesn’t stand still to have its feet worked on, it could be because it’s painful for the animal. Some localized stretching can alleviate the stiffness, protecting both horse and farrier.

“I don’t believe in beating up on a horse,” Larry explains. “I believe in getting in their head and figuring out what’s making them tick.” He tells of turning a horse loose in the arena and just watching him move around for twenty minutes. “You could tell he was sore, so I made up a set of shoes that I felt would change his movement.”

It took Larry two hours to make the corrective shoes, but it was worth it when he watched the horse walk cautiously back into the arena, then take off bucking and kicking. “You could tell he just felt good.”

Larry says he gets his “rush” from fixing things and seeing the animal feeling good and the owner smiling. It often takes a team effort. Larry’s wife, Shari, now offers raindrop therapy and essential oils. That, in combination with Sara’s chiropractic treatments and Cody’s and Larry’s farrier work, can treat the whole horse.

“Every horse’s foot tells a story. You have to learn to read that story. He’s going to tell you where his pain issues are, he’s going to tell you where he’s landing on the ground and how he’s moving and if he’s moving the same continuously every time. That’s probably the hardest thing to teach,” Larry explains. “I’ve been in this my whole life and I’m still learning.”

It’s hard work, too. When Larry speaks to students at the University of Minnesota-Crookston, he honestly tells them that maybe one out of the entire class of more than one hundred “will make it in the industry. It takes someone who eats and sleeps with their horse, really doesn’t have a place to live because they live in the barn. They work their butt off for four years to get their name out there and then they might make it.”

Working around horses is also dangerous. “My kids have seen me put back together twelve million different ways,” Larry says. He tells of getting kicked and breaking his thumb. He wrapped it with vet wrap, finished trimming the horse, then went to the doctor.

Cody, who was with him, laughs, “He was just mad because the horse got him.”

One day Larry set his pant leg on fire working at the forge. Cody lost the end of his thumb training a horse. He also tells of a recent training incident when their training saddle got destroyed – with him in it.

Sara, as a teenager, got two concussions after getting repeatedly bucked off a horse she was determined to ride. Shari finally had to hold her down and firmly state, “No more!” or Sara would have tried again.

“We’re very competitive,” says Sara. It’s an understatement. Larry won the 1994 Better Bull Riders Association finals. Shari was Justin Rookie of the Year for the Minnesota Quarter Horse Association in 2006. Sara is a sponsored professional barrel racer. Cody and Larry have both roped professionally and Cody is now riding saddle broncs.

So where does this tightknit family go with a business so dependent on their individual skills and talents? Larry, admitting that the physicality is taking its toll, says, “I am going to slow down.” Even though he had a hip replaced last spring, Shari is skeptical.

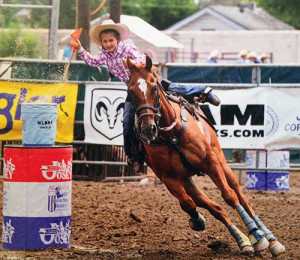

Raegan Graber, 8, is the sixth generation of her family drawn to horsemanship. Here she was competing in the National Little Britches Rodeo in Guthrie, Oklahoma.

Sara explains, “Most people work the first half of their lives trying to build a foundation, which I feel like Dad’s done a beautiful job setting that foundation for us, and the second half trying to build a legacy. That’s what Dad’s trying to do right now. I’m thankful for the foundation, I’m thankful for the hard growing up, I’m thankful for the hard knocks and having to decide what kind of person I wanted to be.”

She wants to instill that passion and teach those life lessons to her own children, and she and Cody ask themselves, “Where are we going with the future of this? We don’t want to let this tradition die, so how can we continue to make it prosperous and grow and bring in those select few, those passionate ones?”

It’s apparent that a sixth generation has already arrived. Sara’s daughter, eight-year-old Raegan Graber, made her second trip to the National Little Britches Finals Rodeo in Guthrie, Oklahoma, in July. Larry says she and his six-year-old grandson Gage Weber “will probably be the ones to pick up the mantle and keep the business going. They both have that passion and they’re most content out in the pasture sitting on the back of a horse.”

Until then, Larry, Cody, and Sara will continue working together, covering an area that measures two hundred fifty square miles. They don’t refer to their customers as clients because, to them, they become family. And that family tradition goes back more than a hundred years.

So you want to get a horse?

So you want to get a horse?

“There’s a lot more to it than people think,” says farrier Larry Curell. Here are some things to consider:

- The personality and temperament of both the horse and the person. “If you’ve got a really soft, gentle person you’re looking for a soft, gentle kind of horse,” explains Larry.

- What do you want to do with your horse? A trail horse is different than a horse used to compete in rodeos or horse shows; a working ranch horse is different than a barrel racing horse.

- Your riding skills. Larry says the biggest mistake he sees is when people buy a young horse “so they can learn with the horse” or their children “can grow up with the horse.” People should learn on a horse that is already trained and reliable. Buying a young horse to learn on is similar to having a teenager learning to drive in a high-powered sports car.

Larry says, “I’m not afraid to tell a person, ‘ That horse will not work for you.’ I’ve seen too many people get hurt or blame it on the horse because their skills don’t match the animal.” That is why his clients have come to appreciate his honesty and trust his judgment. When he sells a horse, it is on a thirty-day trial basis so the new owners can be sure this is the right horse for them.